7 Beams

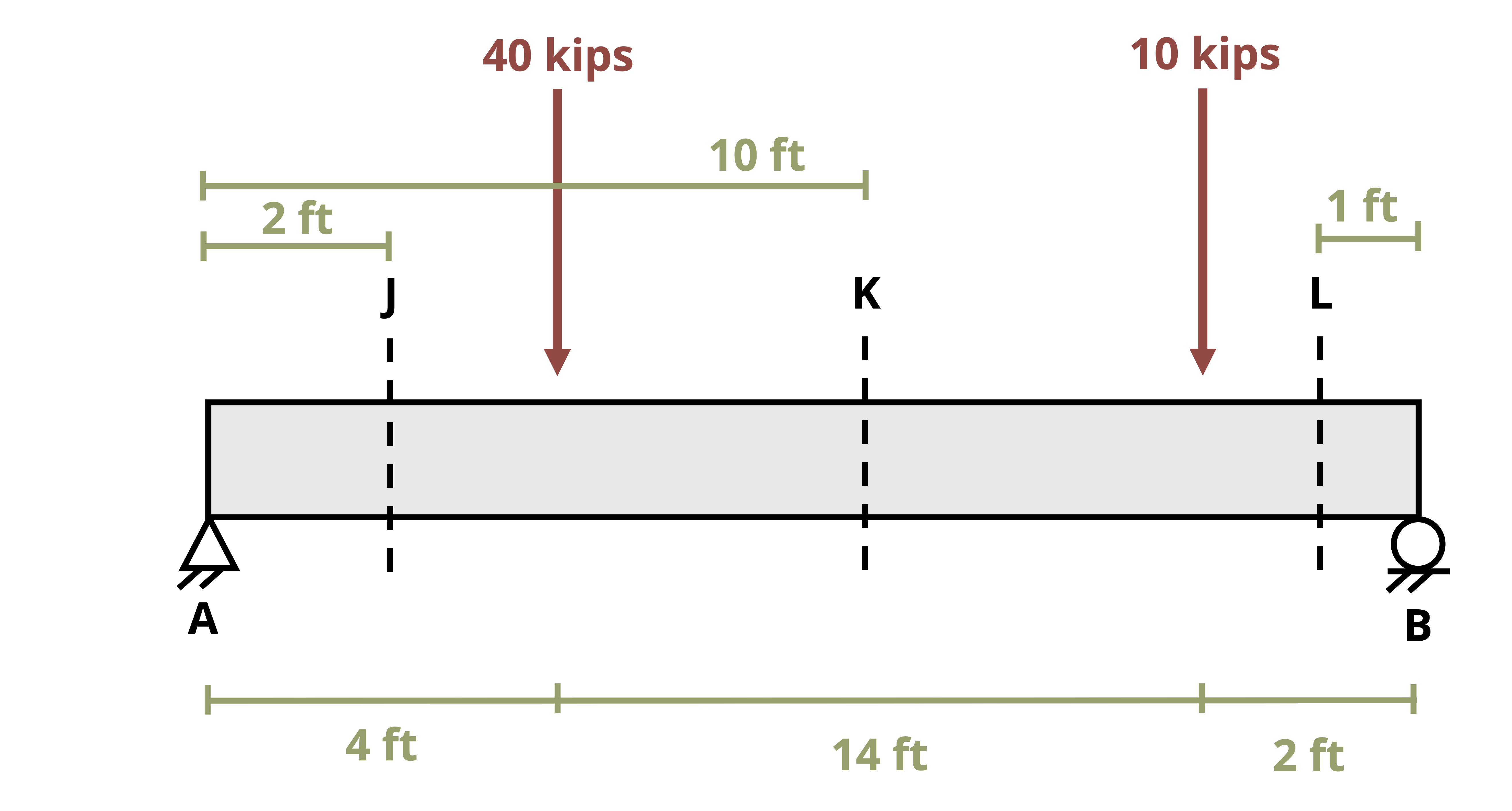

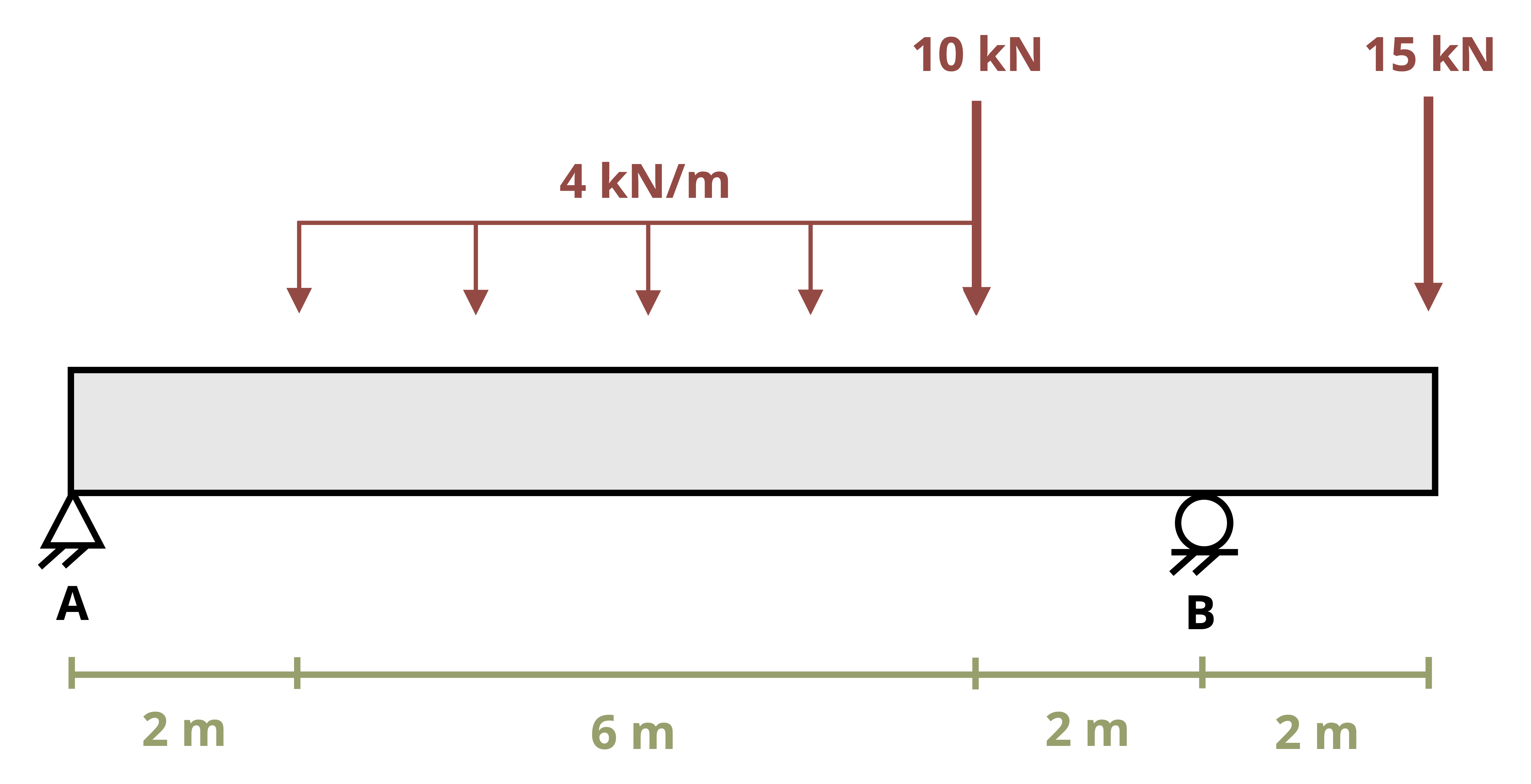

Beams are structural members that support loads along their length. Typically these loads are perpendicular to the axis of the beam and cause only shear and bending moments. Figure 7.1 shows some examples.

As evident in previous chapters, internal forces and moments are crucial to calculating stresses and deflections. The same is true for finding stresses and deflections in beams. Due to the nature of the loadings and constraints of beams, finding internal forces requires new methods in statics. This chapter describes these methods for finding a beam’s internal shear force and bending moments.

Section 7.1 reviews how to find the internal shear force and bending moments at a specific point in a beam using equilibrium. Section 7.2 discusses relationships between the applied load, the internal shear force, and the internal bending moment.

Then follows a discussion of a more general approach to visualizing the internal shear force and bending moment at different points in a beam using diagrams of these. Section 7.3 explores how to draw these diagrams using an equilibrium method. Then Section 7.4 provides an alternative graphical method for drawing these diagrams.

Before presenting methods for finding internal shear and moments of beams, we need to establish a sign convention to provide consistency and act as a guide to interpreting our results. Note that anytime you start a new project or subject, you should ensure that a sign convention is established.

For the purposes of this book, the shear is positive when the external forces shear off as depicted in Figure 7.2. Another way to think about it is that a positive shear is when the internal shear forces cause a clockwise rotation of the beam segment.

The bending moment is positive when the external forces bend the beam in a concave up shape as indicated in Figure 7.2. This causes the top fibers of the beam to be in compression while the bottom fibers are in tension.

7.1 Internal Shear Force and Bending Moment by Equilibrium

Click to expand

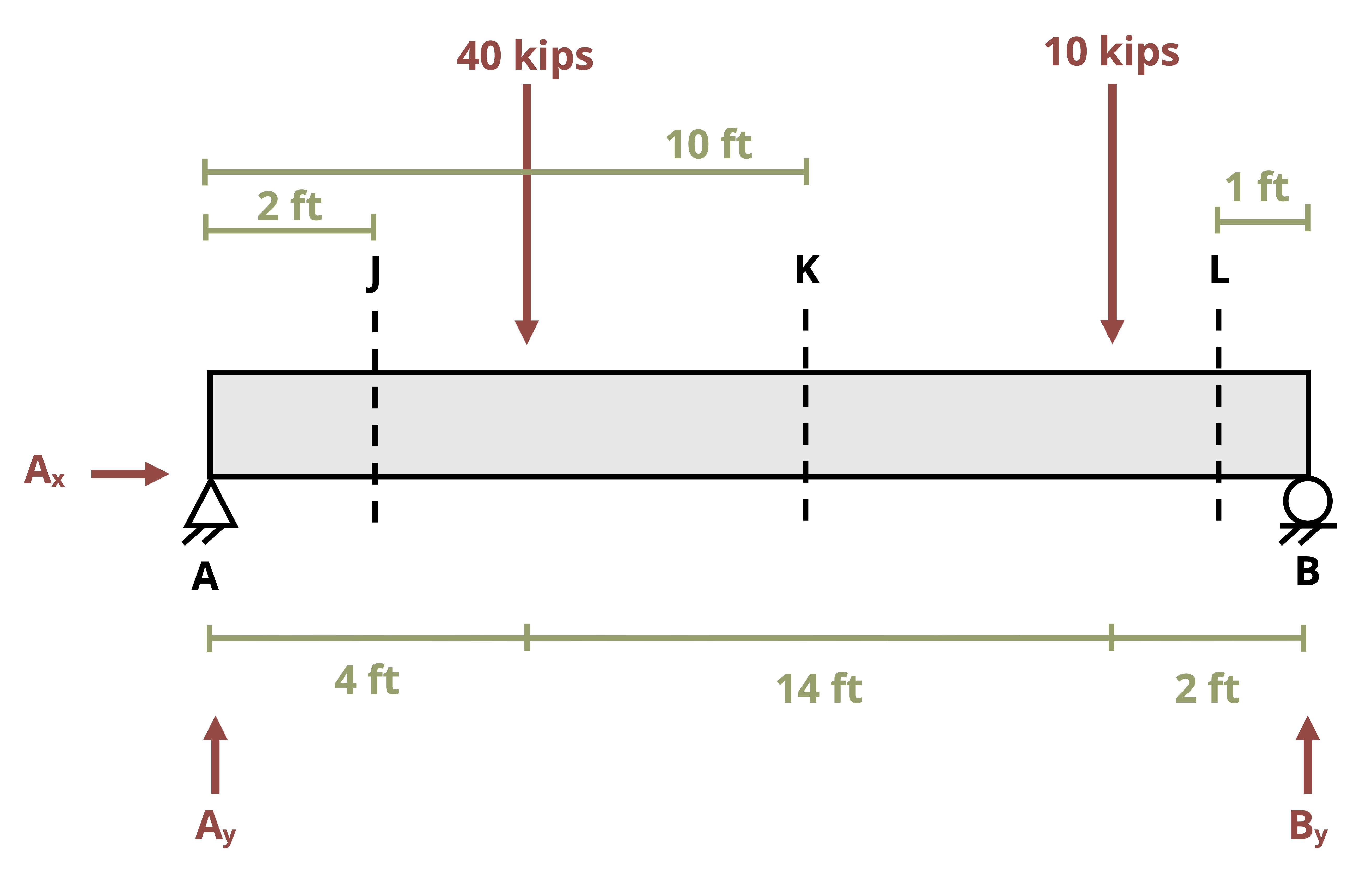

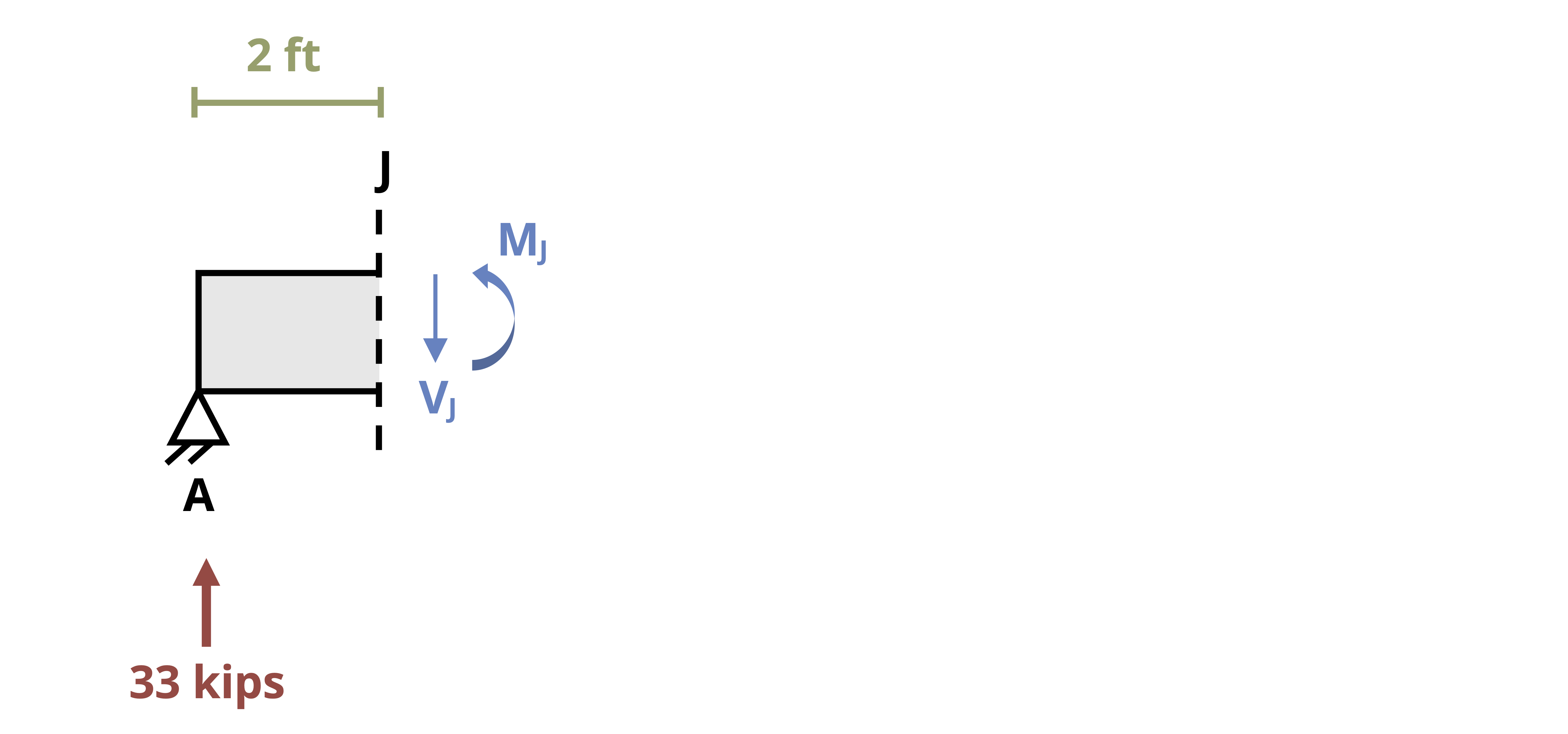

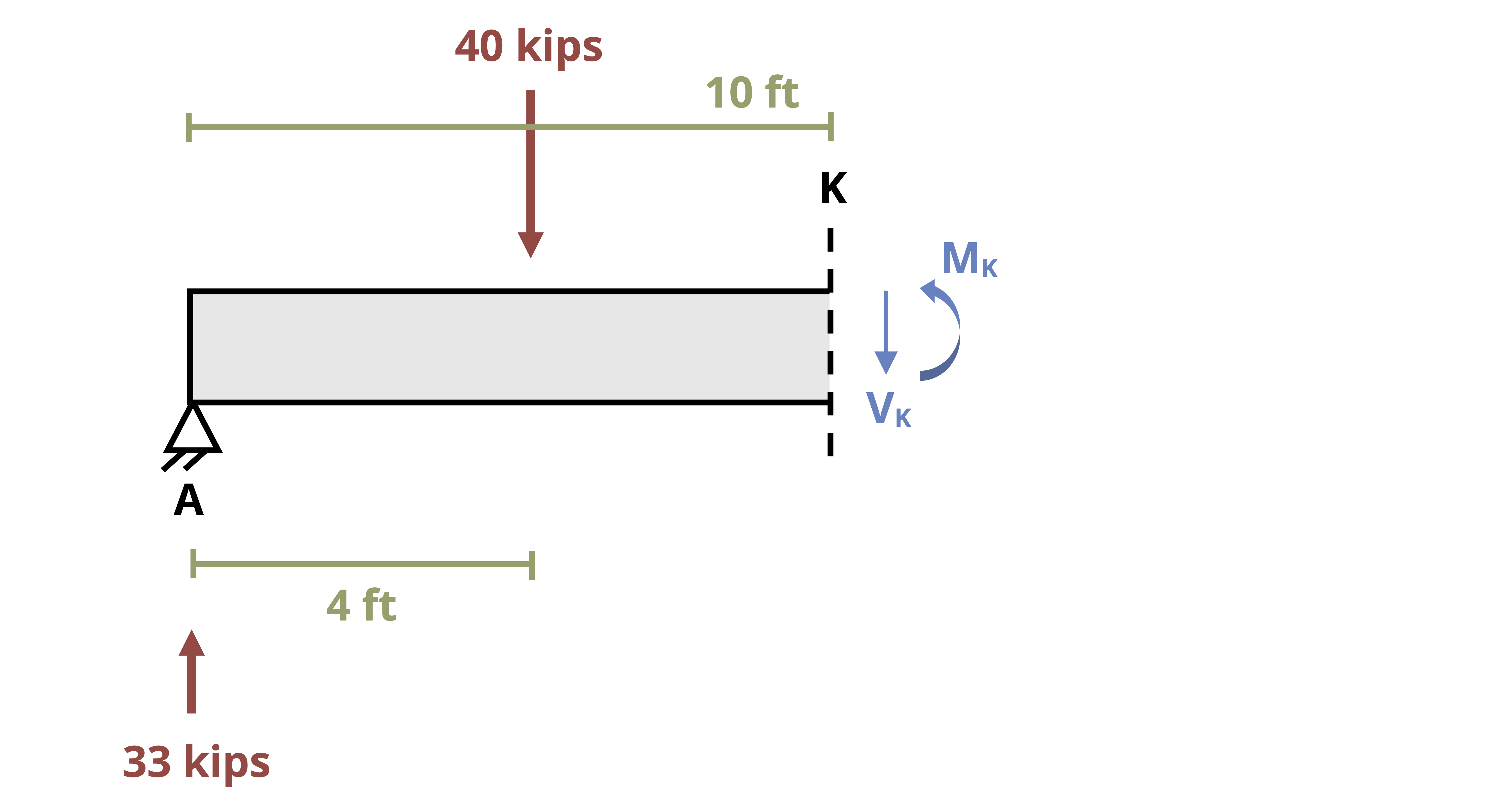

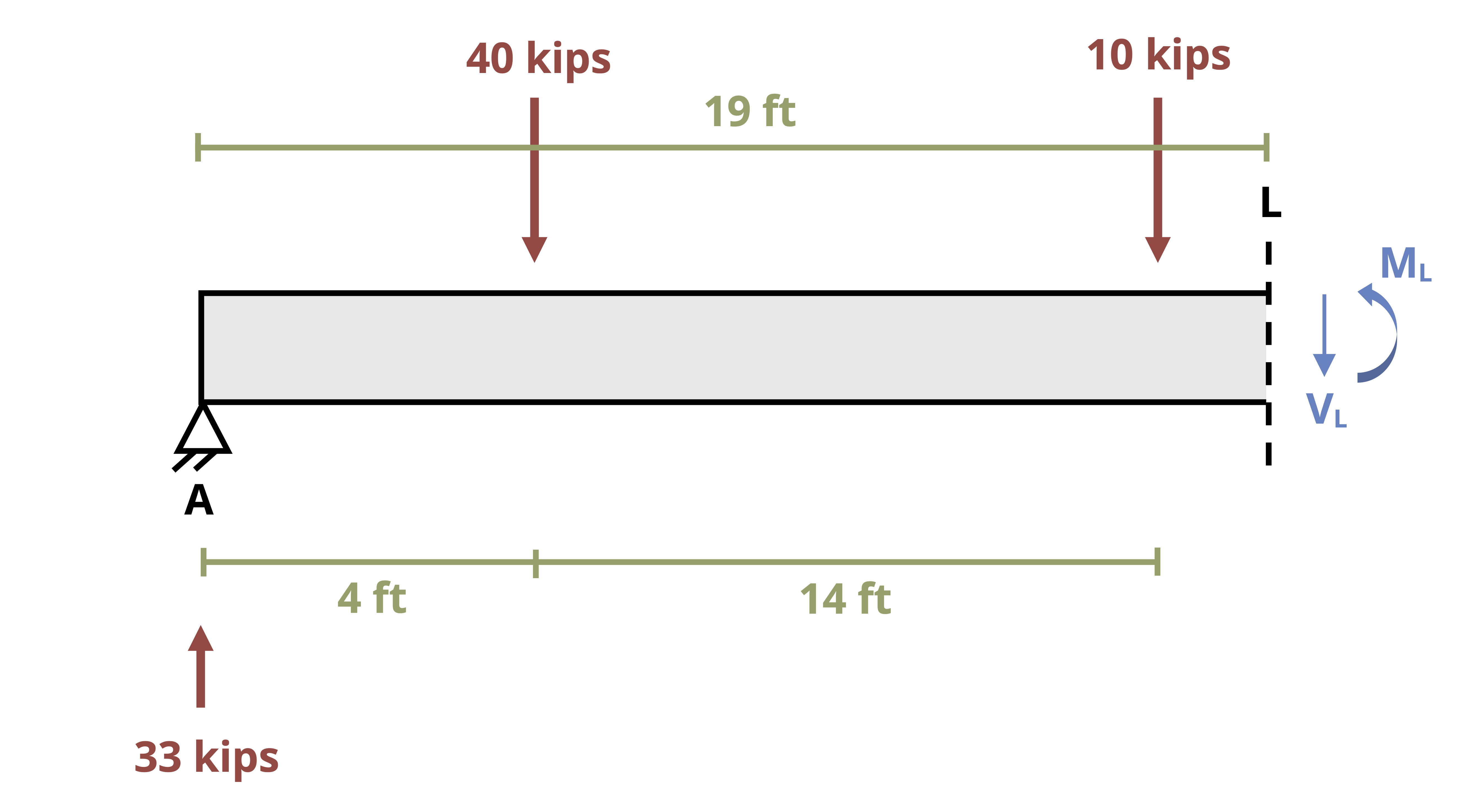

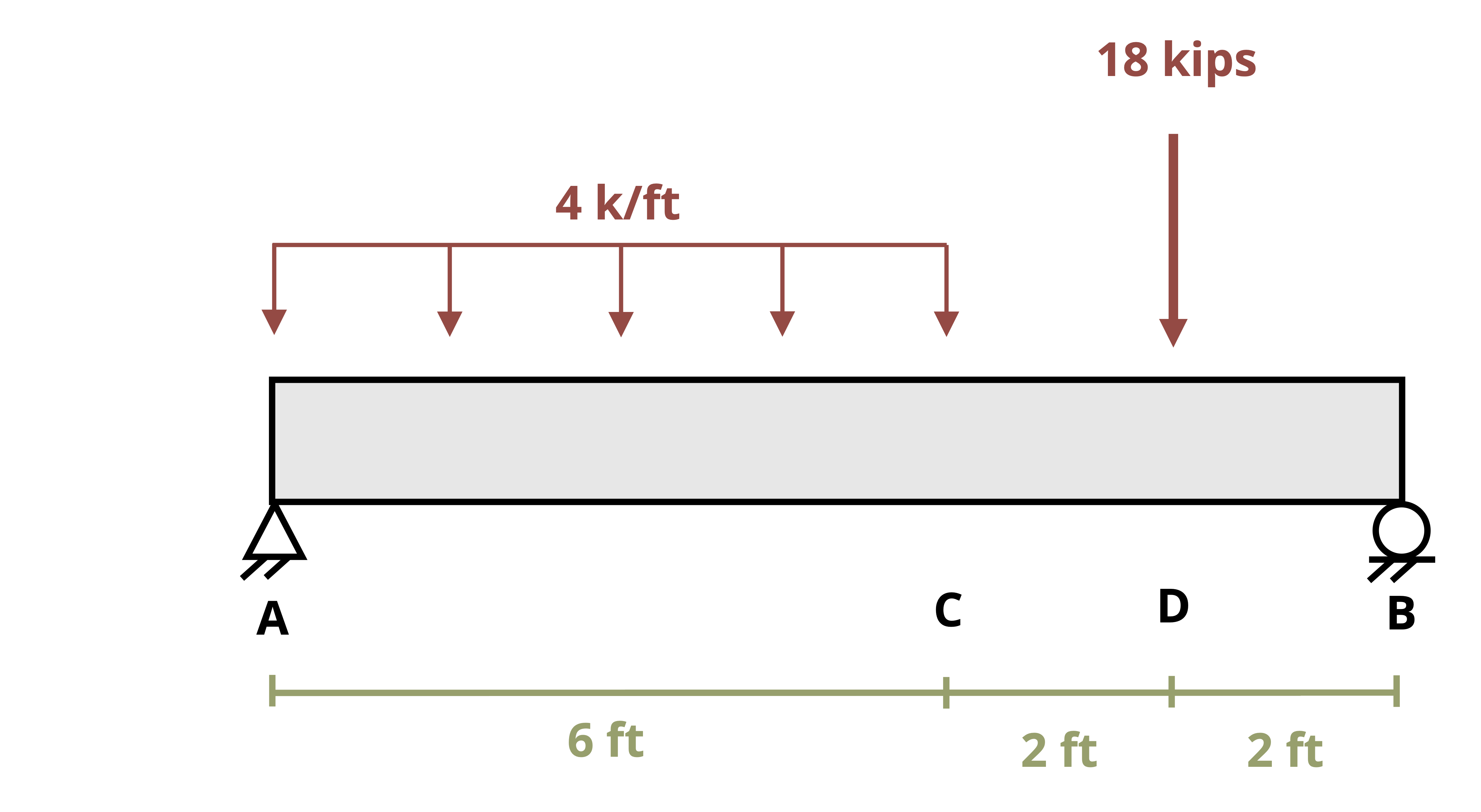

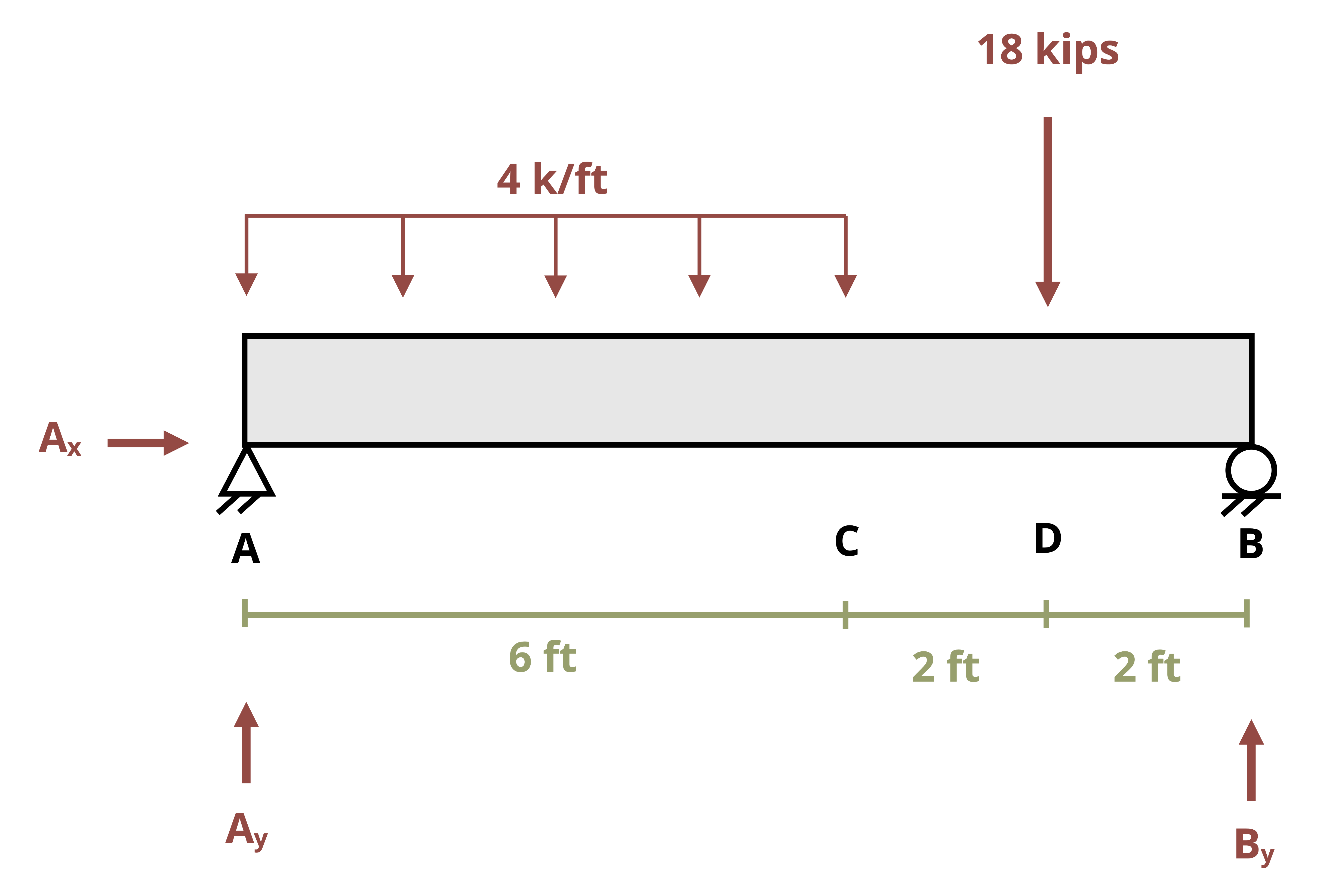

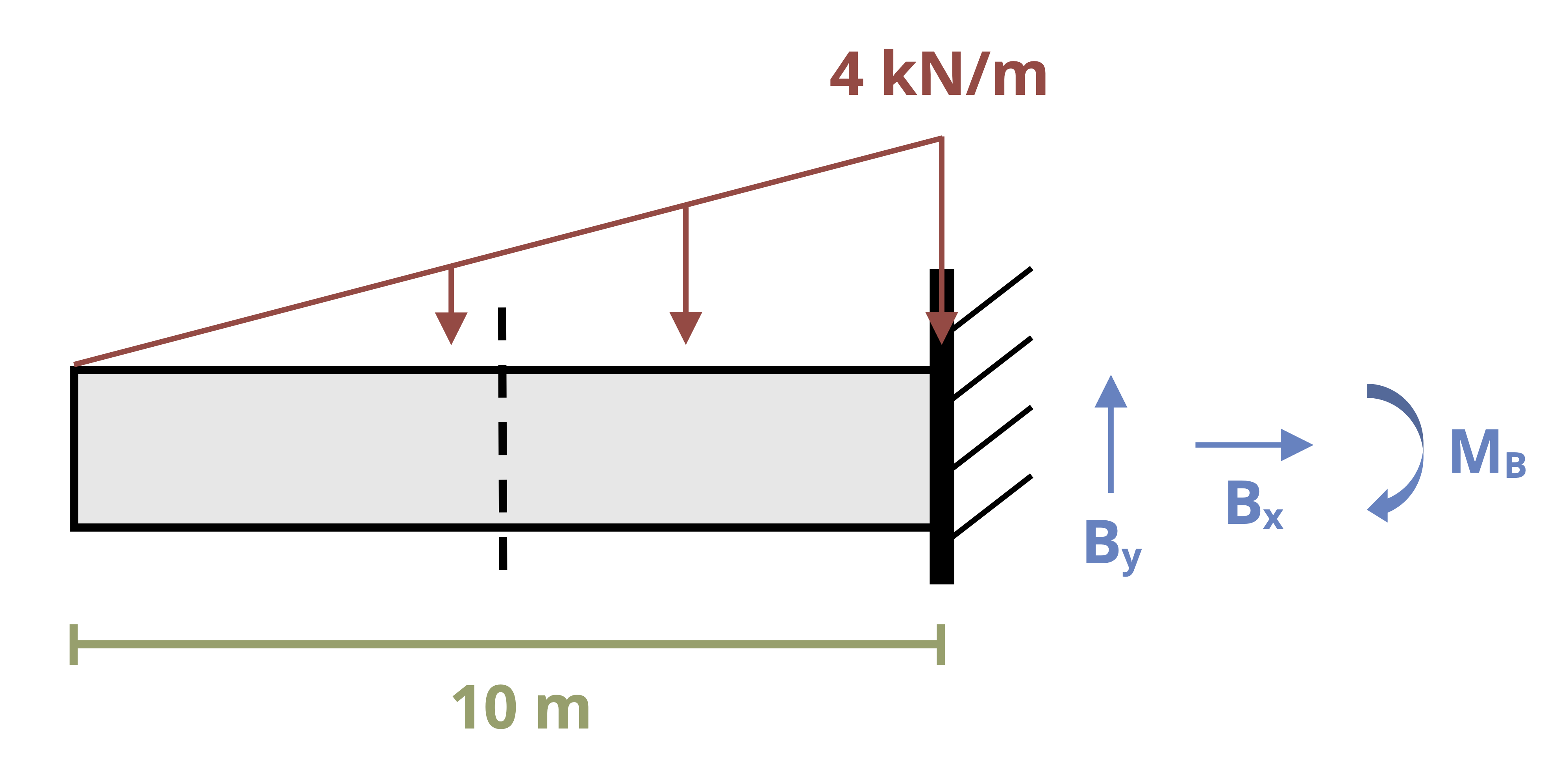

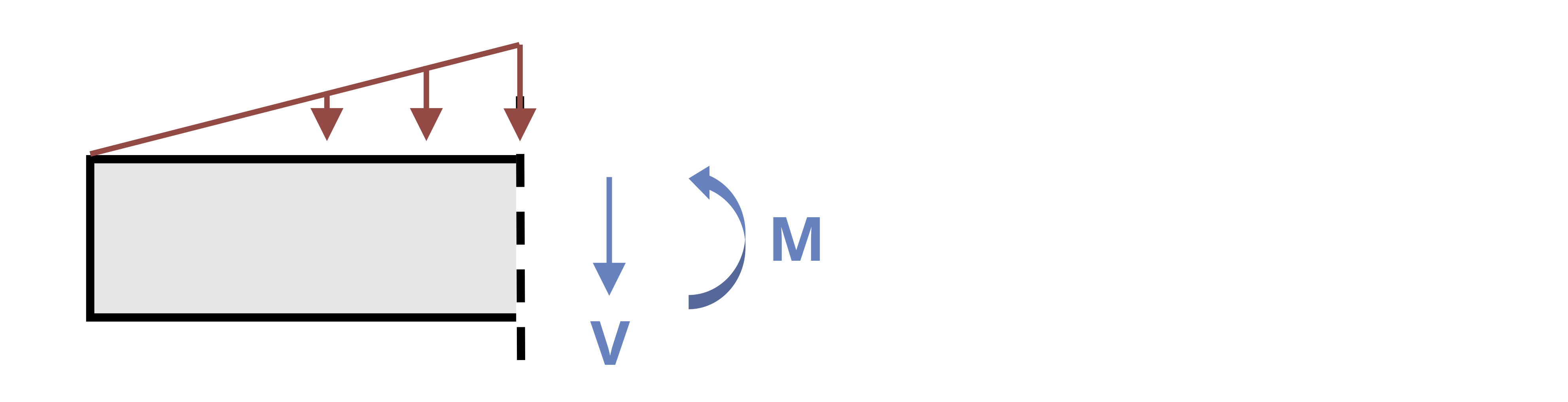

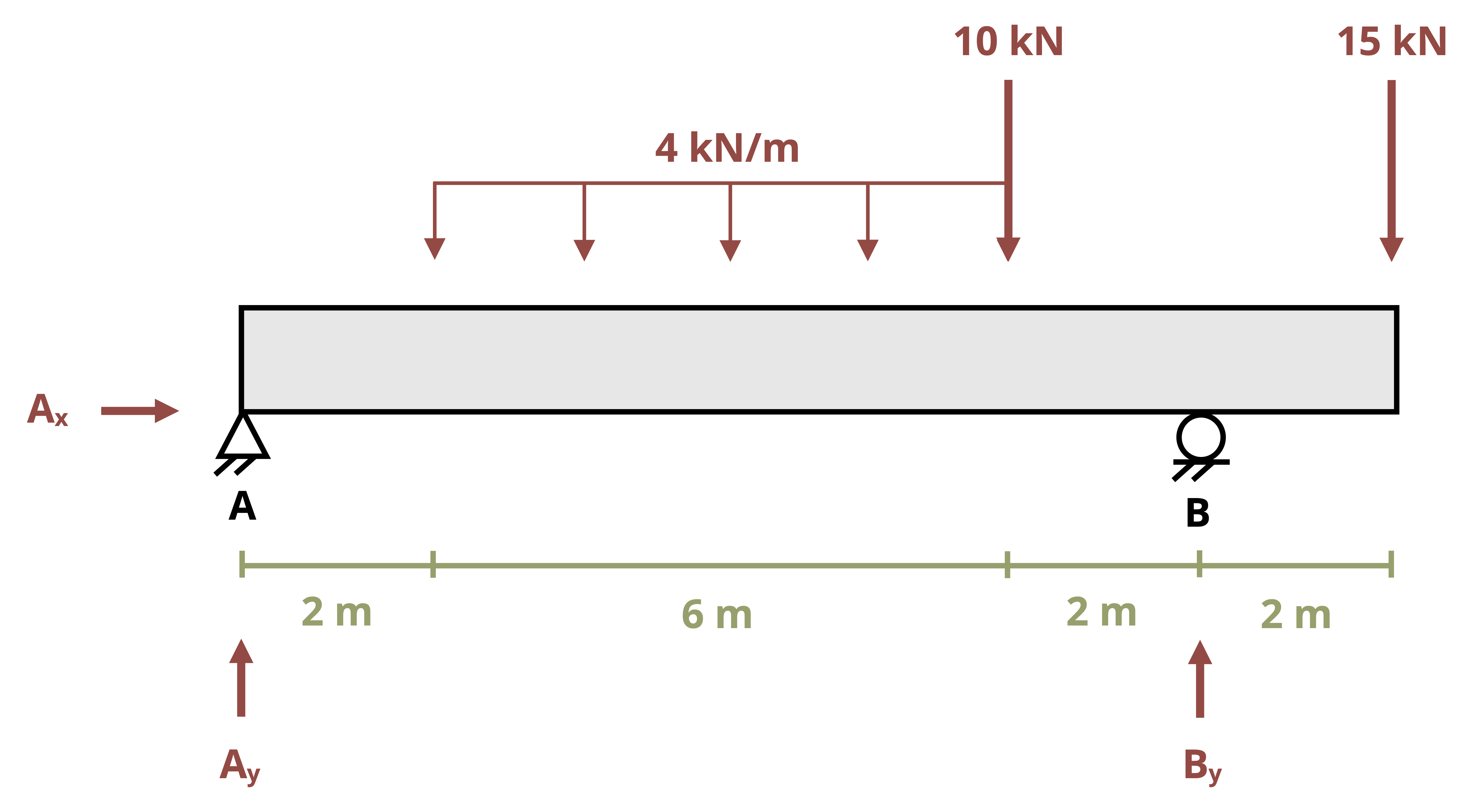

One way to find internal shear and bending forces is to cut sections and analyze the free body diagrams (FBDs), as we did in previous chapters of this book. The first step for a statically determinate beam—one where all forces can be found using only equilibrium equations—is to find the external reactions. To determine the internal forces at any point along the beam, we cut the section at that point and draw the FBD from that point to one end of the beam. We’ll include the internal shear force, V, and internal bending moment, M, at the cut section and then use equilibrium equations to solve for those internal loads. This process is demonstrated in Example 7.1.

7.2 Relationship Between Load, Shear, and Moment

Click to expand

There is a relationship between loading, shear, and moment—and as shown later in this text, slope and deflection—in a beam. Consider the beam in Figure 7.3, which is subjected to a distributed load, w per unit length.

Now look at a small section from that beam that has a width of Δx, shown below. The distributed load has been repalced with a resultant force ΔF (this is indicated by a dashed arrow in the FBD).

Since both sides of the beam have been cut, replace each cut with internal shear and moment forces assuming the positive sign convention established earlier in this chapter.

7.2.1 Relationship Between Load and Shear

This FBD is in static equilibrium, so we can use the equilibrium equation to sum forces in the y direction and set it equal to zero.

\[ \sum F_y=V-\Delta F-(V+\Delta V)=0 \\ \]

\[ \boxed{\Delta V=\Delta F} \tag{7.1}\]

Or \[ \Delta V=w\Delta x \]

Dividing both sides by Δx and then letting Δx approach zero produces

\[ \frac{\Delta V}{\Delta x}=\frac{d V}{d x}=w \]

We then rearrange this by multiplying both sides of the equation by dx.

\[ d V=w d x \]

Now we can integrate between any two points A and B on the beam.

\[ \boxed{\underbrace{\Delta V}_{\substack{\text{change in} \\ \text{shear}}}=\int\underbrace{w d x}_{\substack{\text{area under} \\ \text {loading curve}}}} \tag{7.2}\]

This equation is valid for distributed loads, but not when there is a discontinuity in the shear diagram that is caused by concentrated loads. This relationship should be used only between concentrated loads.

7.2.2 Relationship Between Shear and Moment

Let’s return to the FBD of the small section of the beam subjected to a distributed load. This segment is shown in Figure 7.4. We can apply another static equilibrium equation, summing moments about point C.

\[ \begin{aligned} \sum M_c=0 & =-M-V(\Delta x)+\Delta F\left(\frac{1}{2} \Delta x\right)+(M+\Delta M) \\ \Delta M & =M+V \Delta x-(w \Delta x)\left(\frac{1}{2} \Delta x\right)-M \\ \Delta M & =V \Delta x-\frac{1}{2} w \Delta x^2 \end{aligned} \]

Dividing both sides by Δx and then letting Δx approach zero yields

\[ \boxed{\underbrace{\frac{\Delta M}{\Delta x}}_{\text { Slope of moment diagram}}=\underbrace{V}_{\text {shear }}} \tag{7.3}\]

Then we rearrange this by multiplying both sides of the equation by dx.

\[ d M=V d x \]

Now it is possible to integrate between any two points A and B on the beam.

\[ \boxed{\underbrace{\Delta M}_{\text {Change in moment}}=\underbrace{\int V d x}_{\text {Area under shear diagram }}} \tag{7.4}\]

This equation is invalid at points where a concentrated force or concentrated moment occurs. These concentrated loads cause discontinuities in the moment diagram.

7.2.3 Using Calculus Knowledge to Build Shear and Moment Diagrams

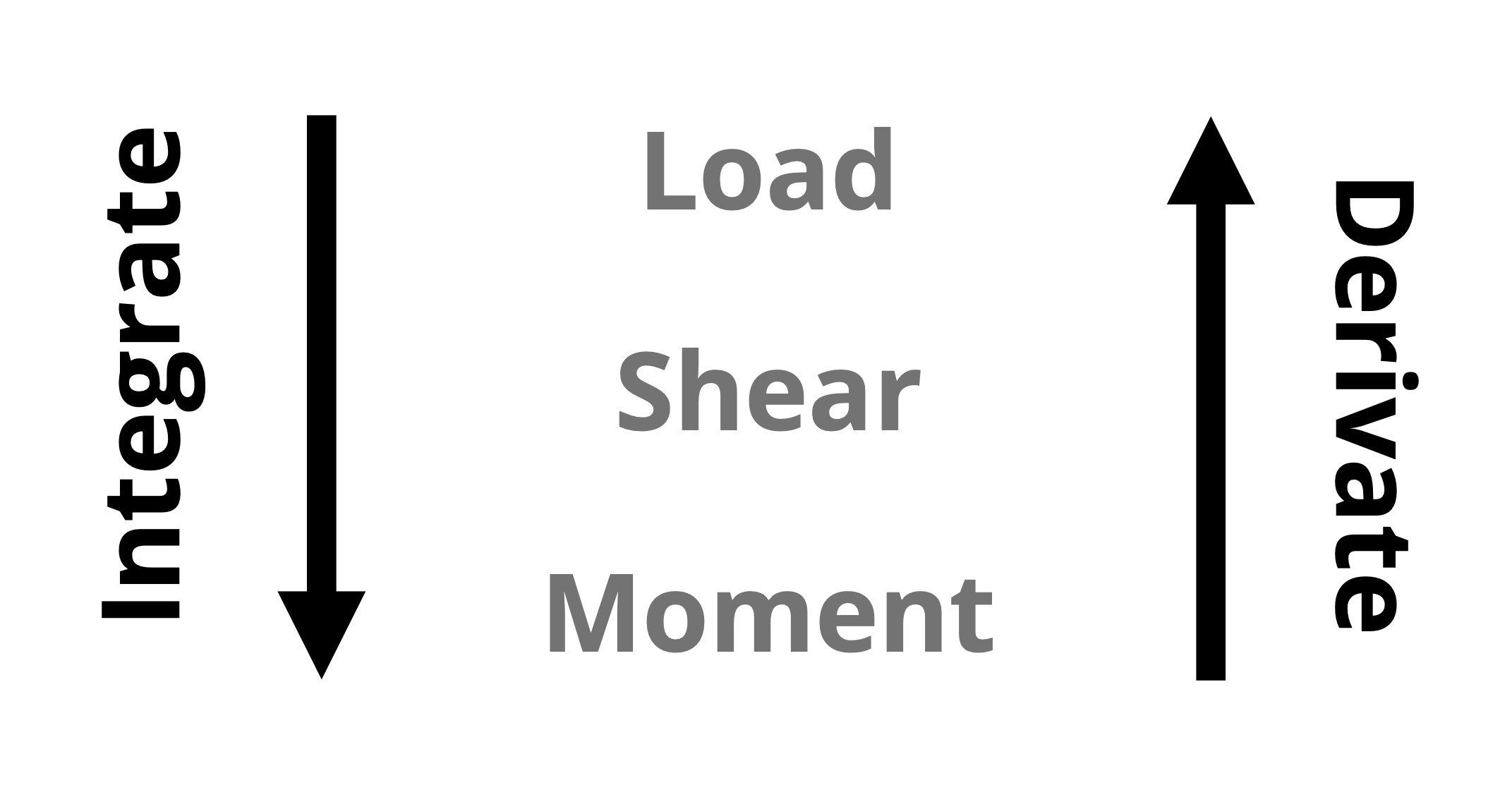

In a basic sense, the relationship between load, shear, and moment can be described as in Figure 7.5.

Combine these relationships with what you know about derivatives and integrals from your calculus course. Here are some items of note:

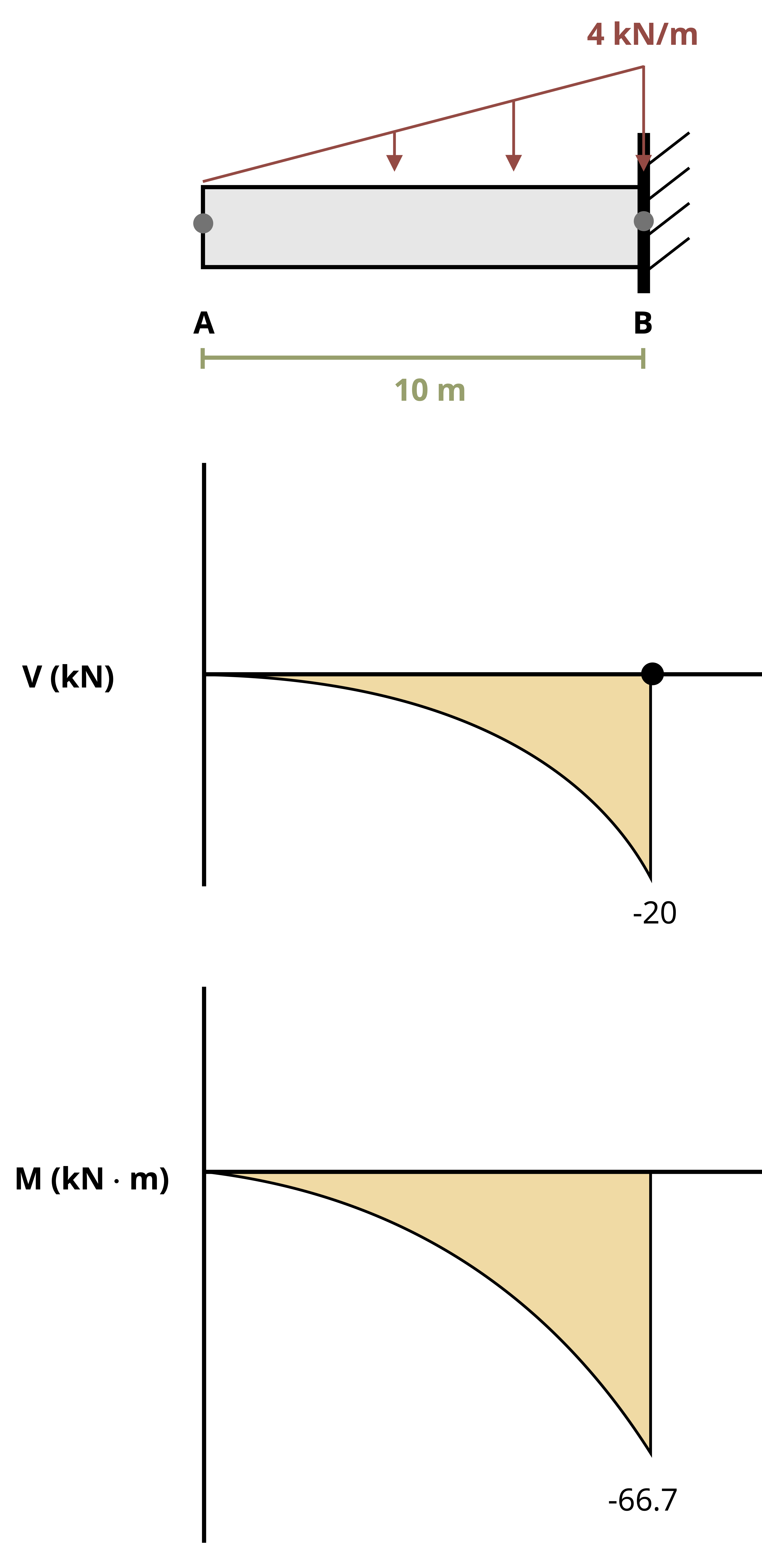

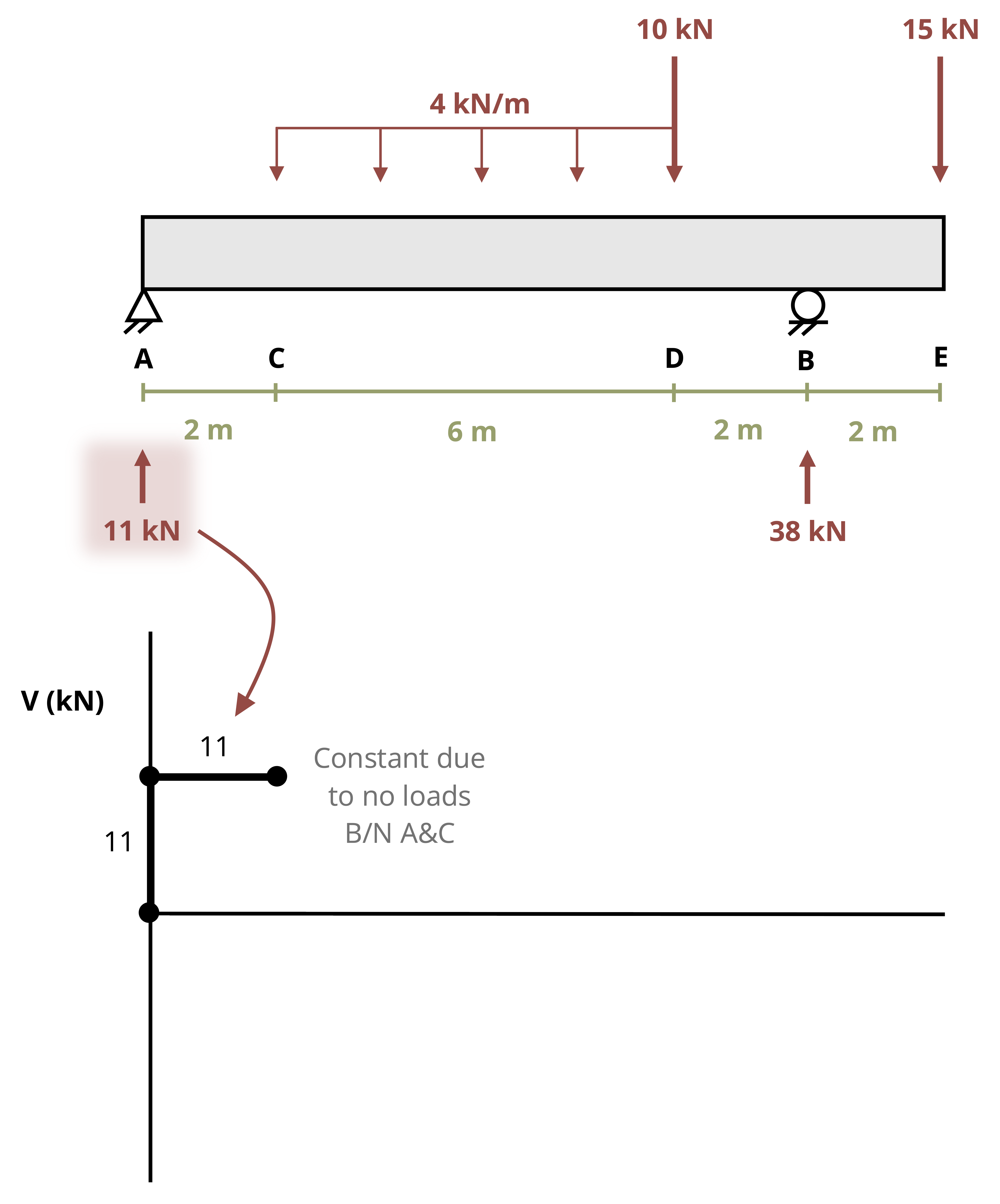

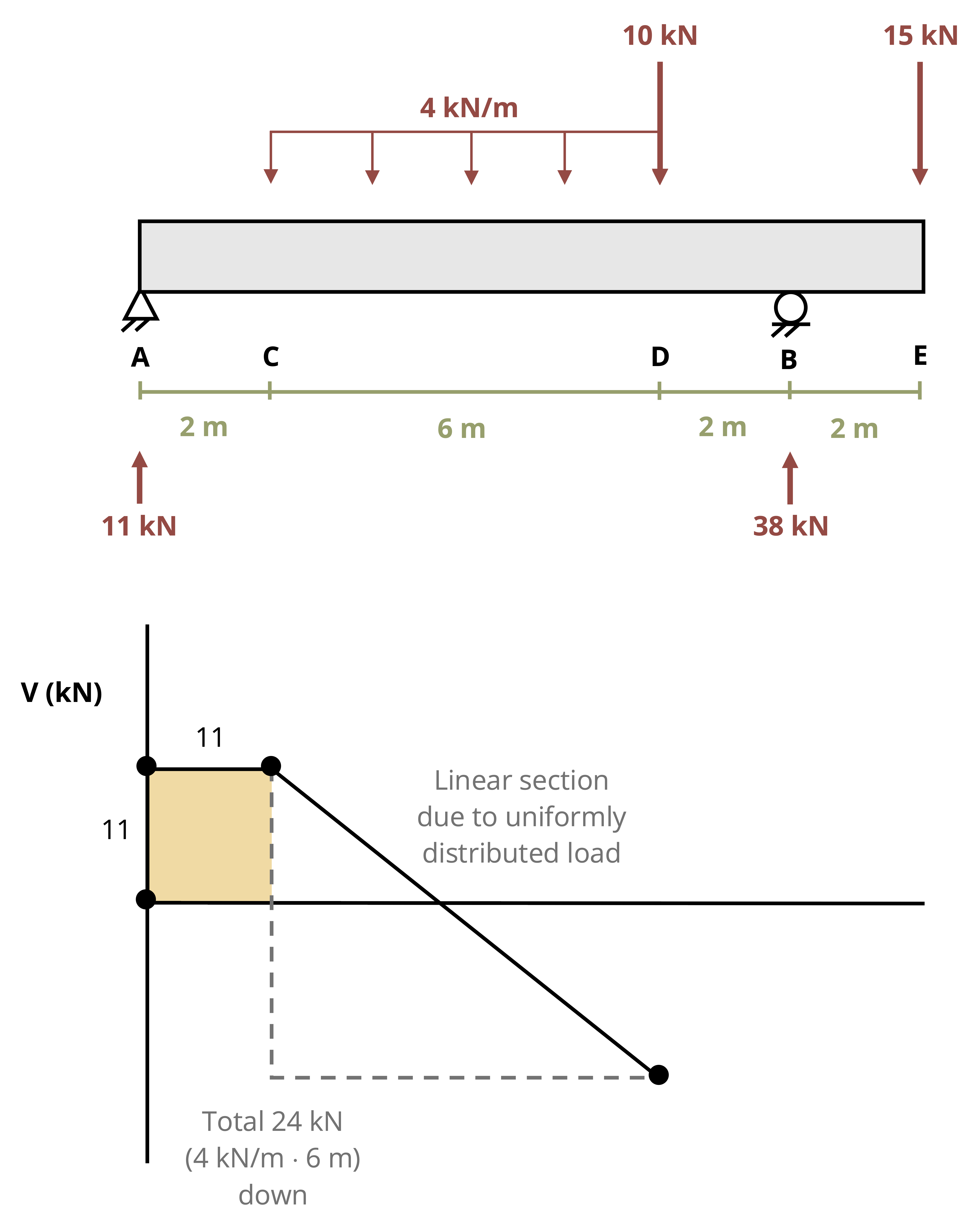

The slope of the shear diagram is equal to the sign and magnitude of the distributed load. If there is no load on a section of the beam, then the slope of the shear diagram is zero.

Similarly, the slope of the moment diagram at any point is the derivative of the moment function evaluated at that point. This is equal to the sign and magnitude of the shear at that point.

The area under the distributed load between two points is equal to the change in the shear between those same two points.

The area under the shear diagram between two points is equal to the change in the moment between those same two points.

The maximum moment occurs where its derivative (shear) is equal to zero.

At the points of concentrated forces, the shear diagram jumps up or down depending on the direction of the force. If the force is up, then the shear diagram will jump up, and if the force is down, the shear diagram will drop down.

At the points of concentrated moments, the moment diagram jumps up or down depending on the direction of the rotation. If the concentrated moment is clockwise, the moment diagram will jump up, and if counterclockwise, it will drop down. This “opposite” direction effect for the internal bending moment is the reaction to the applied moment to stay consistent with the established sign convention. The shear diagram remains unaffected.

If the load can be represented with a polynomial, then we can easily predict the degree of the subsequent shear and moment functions. For example, if the load is a uniformly distributed load (constant), the shear will be a linear function (n + 1) and the moment will be a parabola (n + 2).

Use all you know about calculus and the relationships between functions when you derive and integrate to build, check, and analyze shear and moment diagrams.

7.3 Determining Equations by Equilibrium

Click to expand

The relationship between load, shear, and moment allows us to build complete shear and moment diagrams using a few different methods. We’ll explore two of them: an equilibrium method and a graphical method.

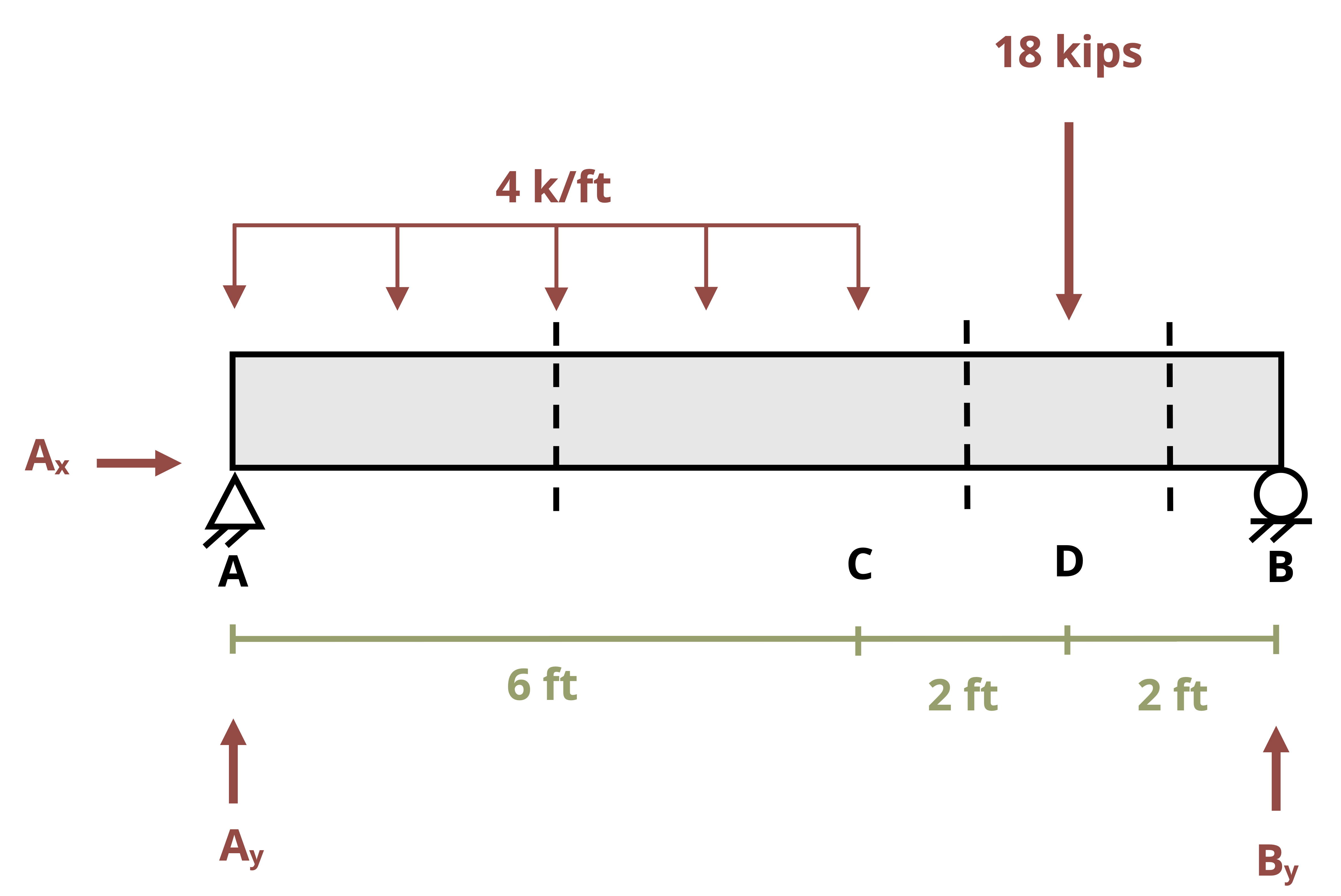

In Section 7.1 we found the internal shear force and bending moment at specific points in the beam by cutting a cross-section at a given point and using equilibrium. The method in this section is similar, but instead of cutting a cross-section at a specific point, we’ll cut a cross-section at distance x from the left end of the beam. We’ll draw an FBD and determine the internal shear force (V) and bending moment (M) as before, but this time the resulting equations for V and M will be functions of distance x.

To draw the diagrams, we can solve this equation at two values of x. It is often simplest to solve when x = 0 and when x = L, the length of the beam. These are two points we can then connect on our diagram. The diagram’s shape depends on the highest power of x that appears in the equation.

For x0 we obtain a flat horizontal line.

For x1 we obtain a straight diagonal line.

For x2 we obtain a curved line.

For x3 we obtain a cubic curve.

If two points are insufficient to determine the exact shape of the curve, simply solve the equations at a third point (e.g., where x = L/2). We can solve the equations at as many points as necessary, but two or three points, along with knowledge of the general shape of the line, are typically sufficient. The equations found using this method are valid as long as the external loading doesn’t change.

Cases where the external loading does change require us to determine a new set of equations each time the loading changes. This includes any time a distributed load begins or ends, and both sides of a concentrated force or couple. In each region of load, we will cut a cross-section at distance x and determine equations for V and M that are valid for that region. We can then solve each equation at values of x at the start and end of their valid region and build up the complete shear force and bending moment diagrams.

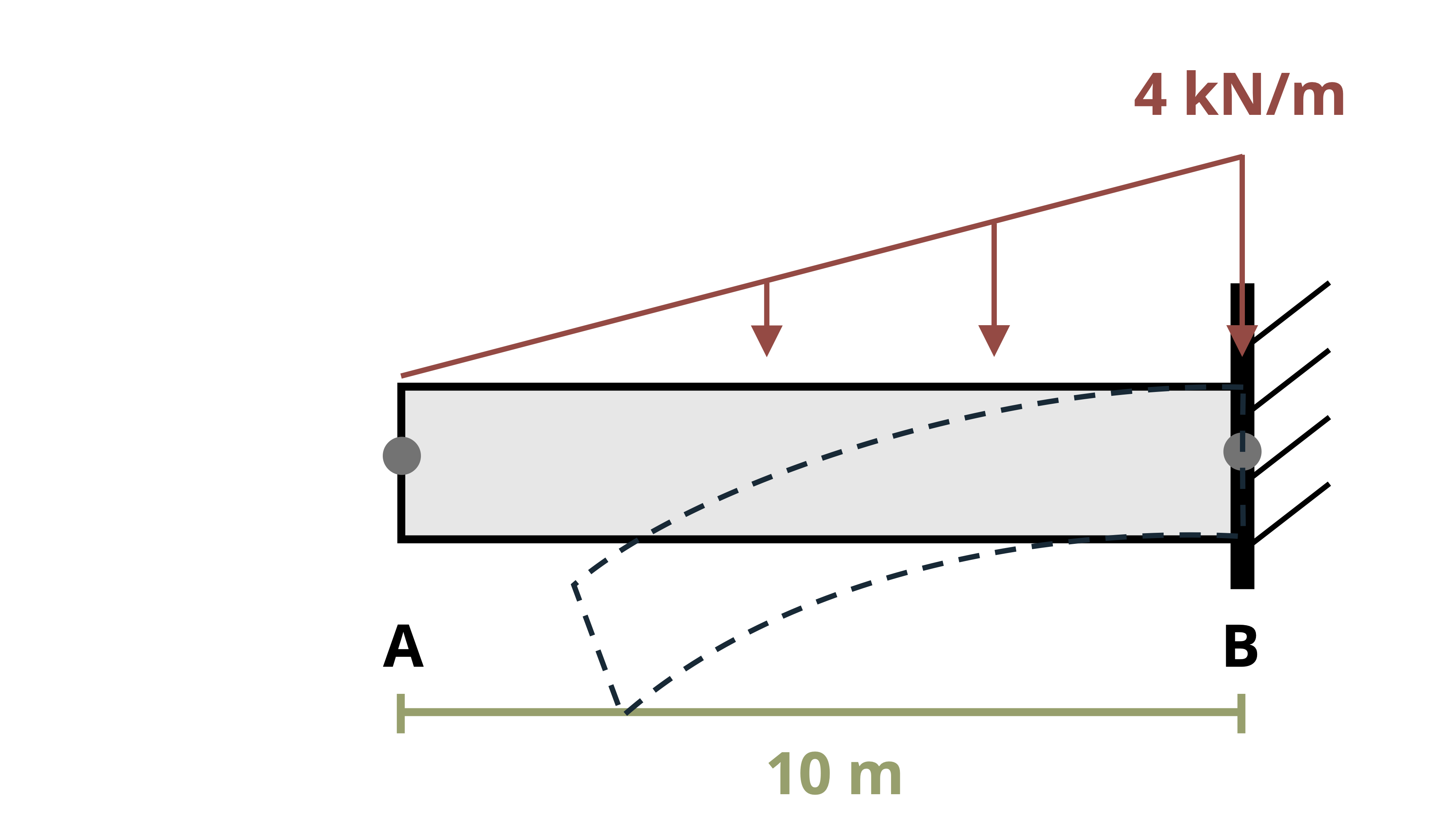

Example 7.2 illustrates this method for a simply supported beam, and Example 7.3 for a cantilever beam.

7.4 Graphical Method Shear Force and Bending Moment Diagrams

Click to expand

An alternative, often faster method for drawing shear force and bending moment diagrams is the graphical method. This approach leverages the relationships between load, shear force, and bending moment, allowing us to derive one diagram from another.

Specifically, Section 7.2 showed that \(\frac{dV}{dx}=w\) and \(\frac{dM}{dx}=V\). That is, the slope of the shear force diagram at any point equals the applied distributed load at that point, and the slope of the bending moment diagram at any point equals the shear force at that point.

Further, any applied concentrated force causes a jump in the shear diagram (e.g., an upward force results in an upward jump). Any applied couples causes a jump in the bending moment diagram (e.g., a clockwise moment causes an upward jump). Thus the shape of the shear force diagram is based on the applied loads, and the shape of the bending moment diagram is based on the shear force diagram.

Finally, Equation 7.2 also showed that the change in shear force between any two points is equal to the area under the distributed load between those same two points. Evident from Equation 7.4 is that the change in bending moment between any two points is equal to the area underneath the shear force diagram between those two points. This allows us to add numbers to the diagrams and determine the value of the shear force and bending moment at key points.

When the loading is relatively simple, consisting of concentrated forces, concentrated moments, and uniformly distributed loads, we can use geometry to find the area of the load and shear diagrams since the shapes are simple. Example 7.4 and Example 7.5 illustrate this method.

Summary

Click to expand

Shear and moment diagrams allow us to calculate and visualize the internal forces of beams. These internal forces are used to calculate stresses and deformations (covered in upcoming chapters). The general procedure for building the shear and moment diagrams is as follows:

- Sketch the beam, replacing support conditions with equivalent force(s).

- Find the support reactions using equilibrium.

- Use the method of equations or geometry or a combination to build the shear diagram directly below your beam sketch.

- Use the method of equations or geometry or a combination to build the moment diagram directly below your shear diagram.

- Ensure that your diagrams are labeled, including units, and that all pertinent values are indicated.

Relationship between load and shear:

\[ \Delta V=\Delta F \] \[ \underbrace{\Delta v}_{\substack{\text{change in} \\ \text{shear}}}=\int\underbrace{w d x}_{\substack{\text{area under} \\ \text {loading curve}}} \]

Relationship between shear and bending:

\[ d M=V d x \] \[ \underbrace{\Delta M}_{\text {Change in moment}}=\underbrace{\int V d x}_{\text {Area under shear diagram }} \]

References

Click to expand

Figures

All figures in this chapter were created by Kindred Grey in 2025 and released under a CC BY license, except for

- Figure 7.1: Examples of structural beams. A: Washington State Dept of Transportation. 2023. CC BY-NC-ND. https://flic.kr/p/2ojECo3. B: Government of Prince Edward Island. 2017. CC BY-NC-ND. https://flic.kr/p/R3NFRw. C: Jack E Boucher. 1985. Public domain. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:FallingwaterCantilever570320cv.jpg.